Why Retired Athletes Make Wine

Drew Bledsoe and Sidney Rice On How Wineries Became the New Car Dealerships

These are the careers I expect from retired athletes:

coach

commentator

underrated-but-still-not-very-good actor

car dealership owner

steak restaurant owner

fishing tour company owner

hapless-but-still-legally-liable partner to a con man

So I’ve been surprised at how many former professional athletes are starting wineries. Which I don’t like.

Jocks are supposed to stay in their world of drinking beer and having sex and leave my world to me. If I cede wine to them, soon they’ll have thoughts on Ulysses and write self-deprecating humor columns.

When this first started a couple of decades ago, I wasn’t threatened, since athletes were just slapping their names on labels of mediocre wines. But now a few of them are putting out great wine. Often, without putting their names on it. Or pictures of sportsballs.

I Zoomed with four-time Pro Bowl NFL quarterback Drew Bledsoe and Super Bowl-winning wide receiver Sidney Rice to find out why they are doing this to me. Both are making wine in Walla Walla, Washington - which is where Bledsoe grew up and not far from where Rice played for the Seattle Seahawks.

Bledsoe produces Doubleback wines, which cost more than $100 and you can only get by signing up for the allocation waitlist. Now that he’s spent 17 years establishing himself in the industry, he felt he could use his name on the new, more reasonably priced Bledsoe Family Winery.

Rice makes Dossier wines and you can buy the $110 Cabernet Sauvignon on his website without any waiting whatsoever.

Bledsoe told me that when he went to Washington State, he drank the cheapest beers he could find. When he left after his junior year to play for the New England Patriots, he tried wine. “We were supposed to be grownups now so we ordered wine with dinner. Me and my wife and a handful of teammates,” he said.

When Rice showed up in Minnesota to play for the Vikings, he drank cocktails. “I’m a young 20-year-old and we were drinking vodka and whiskey. When I was able to get into clubs,” he said. But one teammate, Visanthe Shiancoe, only drank wine. “He was one of those guys who took care of his body.”

I was relieved to hear that when Rice and Bledsoe did get into wine, their jock friends mocked them for it. “I took some grief from my buddies early on because I wrote some tasting notes and talked about lilacs and whetstones and my friends were like, ‘Come on.’’” says Bledsoe.

Even more satisfying was when Bledsoe told me that he still feels out of place in the wine industry. Like when he met up with a wine industry person he wanted to work with. “I pull up in my big diesel truck and she shows up in her Prius. She walks out and, sure enough, she’s wearing a tie-dyed shirt. You got big dumb jock here and hippy earth mother. We would not have been friends in high school. I said ‘We’re screwed. She is predetermined not to like me’,” he said.

Unfortunately it all worked out because Bledsoe is charming and humble and makes great wine. But at least he’s uncomfortable amongst my people.

Athletes, Rice explained, are actually well suited for the high-end wine world. It’s competitive. It’s seasonal. It requires a team. The big difference is that it’s not a zero-sum game.

“In our previous life, we wanted our competitors to lose and lose bad,” said Bledsoe. “But in this business it’s better for me if Dossier kicks ass and if the region makes better wine. There’s an open sharing of information.”

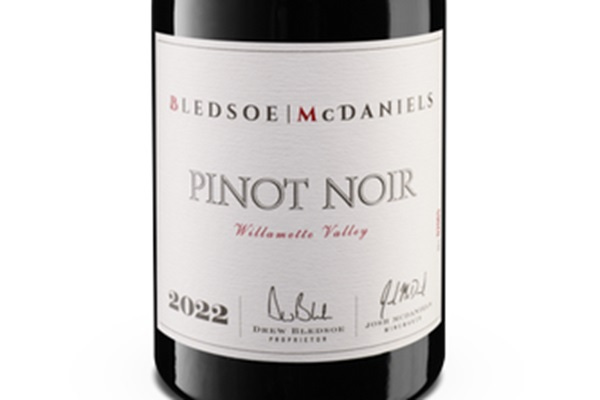

I went to a dinner party with two other couples and brought a bottle of 2022 Bledsoe-McDaniels Pinot Noir and a 2017 Frederic Esmonin Gevrey-Chambertin. Both are 100 percent pinot noir, and would cost vaguely the same amount.

My lovely wife Cassandra and I preferred the Burgundy, which was savory, complex, and quiet in a thinky way. Every single other person overwhelmingly preferred the jock wine. Which did have brighter fruit and more of a wine term called “yumminess.”

The jocks are taking over.